The internal workings of a vast chain of Chinese internment camps used to detain at least a million people from the nation’s Muslim minorities are laid out in leaked Communist Party documents published on Sunday.

The China Cables, a cache of classified government papers, appear to provide the first official glimpse into the structure, daily life and ideological framework behind centres in north-western Xinjiang region that have provoked international condemnation.

Obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and shared with the Guardian, the BBC and 15 other media partners, the documents have been independently assessed by experts who have concluded they are authentic. China said they had been “fabricated”.

However, the documents are consistent with mounting evidence that the country runs detention camps that are secret, involuntary and used for ideological “education transformation”.

When reports surfaced of mass internments without trial, authorities in Beijing initially denied the existence of the detention centres, whose inmates are mostly Uighurs and other ethnic minorities.

After satellite photos and a flood of testimony from former detainees and relatives became impossible to ignore, the party insisted they were for voluntary “vocational training”.

The cables provide apparent confirmation from within China’s bureaucracy that the camps were envisaged from the start as brainwashing detention centres, to be constructed on a massive scale, with inmates confined by multiple layers of security.

This article includes content provided by Scribd. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

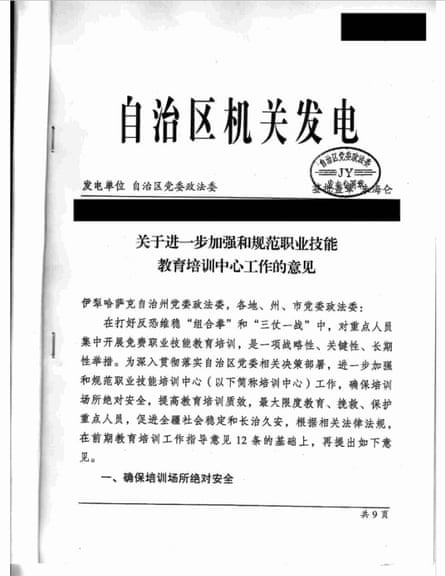

The cache includes a 2017 order, or “telegram”, detailing how the camps in Xinjiang should be built and run.

Signed in the name of Zhu Hailun, the top security official and deputy Communist party chief in Xinjiang, it sets out how the centres were designed to expose detainees to a period of enforced indoctrination.

The document states:

Camps must adhere to a strict system of total physical and mental control, with multiple layers of locks on dormitories, corridors, floors and buildings. Fences should be put around each building, and walls around the compound. A dedicated police station must be at the front gate, all monitored by security guards in watchtowers.

Inmates could be held indefinitely – but must serve at least a year in the camps before they can even be considered for “completion”, or release.

The camps are to be run on a points system. Inmates earn credits for “ideological transformation”, “compliance with discipline” and “study and training”.

Even after completing their “education transformation” inmates are not allowed to go free. They move into another tier of camps, where they face a further three- to six-months’ internment for “labour skills training”.

Weekly phone calls and a monthly video call with relatives are their only contact with the outside world, and they can be suspended as punishment.

“Preventing escape” is a top priority. The order demands round-the-clock video surveillance “with no blind spots” to monitor every moment of an inmates’ day. Control of every aspect of their lives is so comprehensive that they have to be assigned a specific place not only in dormitories and classrooms, but even in the lunchtime queue.

There have been multiple accounts by people who passed through camps of torture, rape and abuse. In an apparent sign of concern about the consequences of mistreatment, Zhu’s order instructs staff to “never allow abnormal deaths”.

Many details match accounts given by former camp inmates. They also provide striking new insights – among them the minimum 12-month term of confinement, and the fact that there are two tiers of camps.

The first seems focused on ideology and Mandarin-language skills; those approved to leave face another three to six months of “labour skills training” in a second detention centre.

There have been multiple credible reports of forced labour in Xinjiang, as part of the government camp system. Some of those who “complete” the re-education systems might be forced to work in these second tier of camps.

The order also suggests former detainees remain under surveillance even after release, with local security and judicial officials told that “students should not leave the line of sight for one year”.

Chinese authorities deny they run detention centres and say the “vocational education and training centres” are part of a focused crackdown on extremism and terrorism.

In 2009, nearly 200 people, most of them Han Chinese, died during riots in the regional capital, Urumqi. Dozens more were then killed and hundreds injured in a series of terror attacks in cities across Xinjiang and beyond. Uighurs have also fought with extremist militant groups abroad, including joining Isis in Iraq.

The document makes clear that as the internment camps went up, authorities were already worried about the scale of their incarceration programme becoming known, even inside Chinese official hierarchies.

The document demands “strict secrecy”, and in addition to a predictable ban on videos and cameras, staff are also ordered not to aggregate important data, preventing even those inside the system from understanding its full extent.

“The work policy of the vocational skills education and training centres are strong and highly sensitive,” the order says. “It is necessary to strengthen the staff’s awareness of staying secret, serious political discipline and secrecy discipline.”

In addition to the order about the camps, the cache includes four “bulletins” that offer a rare insight into the scale of the crackdown and the digital dragnet that powers it.

The bulletins were sent out to update officials and guide their use of the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), the heart of the surveillance system.

They say that in one single week in June 2017, the system flagged up more than 24,000 “suspicious persons” in the four southern districts of Xinjiang alone. Two-thirds of them were detained, with more than 15,600 sent into the re-education camps and 706 sent to jail.

A further 2,096 people were put under surveillance and 5,508 were “temporarily unable to be detained” – suggesting they were destined for camps in future.

One of the bulletins discusses screening 1.9 million Xinjiang users of a file-sharing app. More than 40,000 of the people who used it were considered suspicious or had been labelled potentially “harmful”.

A separate document is a Uighur-language transcript of a trial, not classified but extremely unusual in a region where secrecy means court documents are rarely publicly available.

Together they provide insights into the construction and operation of a comprehensive government campaign that has led to the largest mass internment of an ethnic-religious minority since the second world war, targeting the Uighur minority, along with other mostly Muslim ethnic groups.

Chinese authorities have split up families, targeted the Uighur language and culture for suppression, razed cultural and historic sites and criticised even mild expression of Muslim identity, micromanaging everything from beard length to babies’ names.

Critics say the campaign apparently aims to obliterate Uighur heritage, society and cultural and religious identity.

“The purpose [of the camp network] was to try to indoctrinate and change an entire population by channeling them through this dedicated system,” said Adrian Zenz, a leading researcher into the Xinjiang internment camps, who is senior fellow in China studies at the victims of communism foundation.

Zenz, who has reviewed the documents, described them as “a very important confirmation” of the nature of the system. “[The Chinese government] has been dishonest about the fact that these people are not voluntarily there, they’re forced to be there,” he added.

The order about the camps, and the security bulletins, are classified “secret”, the middle of China’s three levels of classification. Experts verified their language, formatting and contents.

“Chinese classified documents have a very particular structure. And these documents adhere 100% to all of the classified document templates that I’ve ever seen,” said James Mulvenon, an expert in the verification of Chinese government documents who serves as the director of intelligence integration at SOS International.

“From my professional expertise, these documents are very authentic,” he said, adding that their labelling as ji mi, or secret, meant this was more than routine government secrecy. “These are serious classified documents.”

China’s embassy in London said in a statement “the so called leaked documents are pure fabrication and fake news”, and added: “There are no such documents or orders for the so-called ‘detention camps’. Vocational education and training centres have been established for the prevention of terrorism.”

It also said that “trainees could go home regularly”, including to care for children, and that “religious freedom is fully respected in Xinjiang”. The full statement can be found here.

Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian contributed reporting